One of the treasures of any country is its people. In this respect Myanmar, particularly the east with its rich and diverse ethnic minorities, is well endowed. One of the most striking of these groups is the Padaung. Natives of Kayah State the Padaung are seldom seen in the lowlands and, if they appear at all, tend to congregate around the provincial town of Loikaw near the border with Thailand.

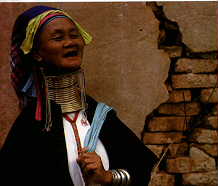

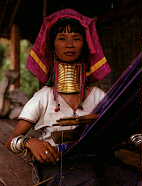

Although the Padaung, a Mongolian tribe who have been assimilated into the Karen group, only number about 7,000 they have attracted a great deal of interest because of their practice of neck-stretching. The custom is more than just a rare and strange expression of feminine beauty, the number and value of the rings confers status and respect on the wearer’s family.

In the past Padaung girls were fitted with the rings at the age of five or six. The day chosen for this ritual was prescribed by the horoscopic findings of the village shamans. The neck was carefully smeared with a salve and massage for several hours, after which a priest would fit small cushions under the first ring-usually made of bronze – to prevent soreness. The cushions were removed later on. The process would continue with successive ring being added every two years. A Padaung women of marriageable age will probably have had her neck extended by aboui 25 cms.

These severe decorations express the Padaung women’s own concept of beauty and social ranking but there are other theories concerning the origins ofthese rings. It has been claimed that rings were first placed around the women’s necks in order to make them undesirable to slave traders. A Padaung legend explains that the rings were protection against tiger bites, a constant hazard in their homeland in the north of China.

Unlike normal accessories, these rings are for life and may only be removed with the direst of results. Adultery among Padaung women has always been punished by the removal of the rings, a fate almost literally, worse than death. This is an unusually cruel punishment as the cervical vertebrae has become deformed after years of wearing the rings, and the neck muscles have atrophied. Unless she wishes to risk suffocation the unfortunate wife must pay for the infidelity by spending the rest of her life lying down or try to find some other artificial support for her neck.

Bronze and silver bracelets also cover the womens legs and arms, a custom likely to remain. The neck rings however, may very well become extinct within a generation or two as younger Padaung women are beginning to refuse to fit the rings around their children’s necks.

The Padaung like to live in river valleys wherever they can. Unlike other tribes these ‘Long-Knecked Karen’ rarely leave their villages. If you want to see them, you have to go to them. The age of a village can often be reckoned from the size of its jackfruit trees. In the village I visited they were tall and fulsome indicating a certain passage of time. Houses stood in small, neat squares made of woven and split bamboo with palm leaf roofs. Each home had a spacious, open terrace where the Padaung sat in the shade in front to their looms, spinning and weaving cotton textiles, blankets and tunics. Some of the bamboo walls were stained blue where cloth had been hung to dry. The Padaung men were conspicuous by their absence, out in the fields tending crops.

At first glance, the Padaung appear to belong to a different continent than Asia, their green and purple headresses, white caftans and shining ornaments suggesting some African tribe or even the Plain Indians of old. Whatever you think of their customs, ‘striking’ is certainly the word to describe the Padaung of eastern Myanmar. It remains to be seen though, whether the Padaung will eventually come are small and containable but this may change. At the moment they appear to welcome the odd visitor, smiling shyly at the cameras, patiently answering the questions that are put to them through the tour guides. How they will keep this dignity and composure in the face of encroaching tourism is a problem shared by all the minority tribes of this region.

Stephen Mansfield